The Power of an Image - by John Pardey

John Pardey, author of '20/20: TWENTY GREAT HOUSES OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY', considers the Power of an Image in shaping architects' and buildings' legacies.

The journey that led to my book began nearly five years ago on yet another trip to visit one of the most celebrated houses of the last one hundred years; this time it was ‘Fallingwater’, on PA Route 381 out of Pittsburgh in the States. Although I knew the house inside out and must have read nearly everything printed about it, as an architect I know that only actually experiencing a building allows you to really understand it – to feel it.

It is of course a beguiling edifice, perched above a small waterfall that seemed to gush from the house itself. But once within, it disappointed greatly. While the exterior is powerful and assertive with its limited palette of stone, render and Cherokee red metal window frames united into an organic entity with sculptural force, once inside its architect Frank Lloyd Wright imprints his values on every single detail; it is fussy, overwrought, and plain annoying – the waterfall can be heard but not seen, light is a glaring strip on three sides, the floor is uncomfortably uneven and the ceiling remarkably low.

Daring to judge such an incredible work from one of the most important architects seemed presumptuous, but we learn from others’ buildings and my disappointment haunted me that night, as I was kept awake in a motel nearby by a fierce thunderstorm that culminated in a lightning strike just outside the open patio doors that saw the tree explode with a deafening crack, and splinters in red, yellow and green fly into the room. I started to write about my experience that night and never stopped until this book was completed. But my insistence to have plenty of images of the twenty houses documented was to cause a two year delay as my publisher and myself sought image permissions – one of the most complicated, opaque and frustrating ventures I can recall.

I blame the 25-year-old photographer Bill Hedrich who donned a pair of waders back in 1937 and standing in the icy cold waters of Bear Run looking up at Fallingwater, took one of the most celebrated photographs in architecture that was for me, love at first sight. The photograph was to feature in Time magazine the following year, where it announced Frank Lloyd Wright as ‘the greatest architect of the 20th century’.

The power of the printed image in the 20th century is hard to overstate. Many architects’ careers were transformed overnight by a single photograph of a finished building: the 27-year-old Charles Gwathmey, who was not even a qualified architect when he designed his first house for his wonderfully trusting and artistic parents on Long Island that was completed in 1965, was launched into the top drawer in the States and a list of rich and famous clients, such as Steven Spielberg, followed.

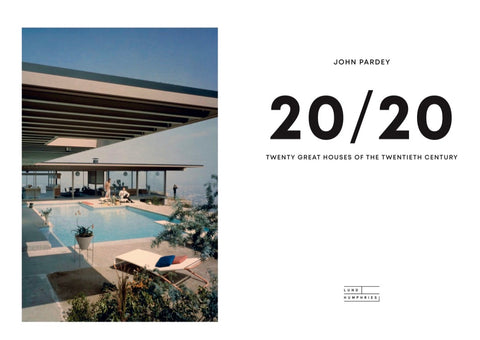

The first image in 20/20 is a photograph of what is generally known as ‘Case Study House 22’ (The Stahl House), 1960. It was taken by Julius Shulman, a photographer who documented the Californian born ‘Mid-century modern’ that was to spread around the world. The house, perched on a steep hillside in Los Angeles was designed by the 35 year-old Pierre Koenig for his baseball star client Buck Stahl. Koenig had a late start as he had served in the army during the Second World War, seeing action in France and Germany before settling back into his life as an architect, and Shulman’s photographs were to make him an international star. The photograph captured perfectly the modest single-storey house wrapped around a pool, set upon the edge of a precipice. It encapsulated the American dream – friends chatting by the pool, blue skies, open plan living and the city of LA spreading away below to the horizon.

A second photograph, taken later that day, was to become the most iconic image of that generation. So much so, that architect Norman Foster was to relate,

‘I am thinking, of course, of the heroic night-time view of Pierre Koenig’s Case Study House 22 which seems so memorably to capture the whole spirit of late 20th century architecture. There, hovering almost weightlessly above the bright lights of Los Angeles spread out like a carpet below, is an elegant, light, economical and transparent enclosure whose simplicity belies the rigorous process of investigation that made it possible. If I had to choose one snapshot, one architectural moment, of which I would like to have been the author, this is surely it.’

Shulman had become successful many years before and a single image of Richard Neutra’s Desert House in Palm Springs was to immortalise that house – for me, the greatest house of the century. The photograph was taken at dusk as Liliane – the wife of Edgar Kaufmann, the client of Fallingwater – reclines by the pool masking a bright light behind her, capturing the promise of outdoor living, with sun chairs, pool, mountains and walls dissolving into nothing. This photograph made the pages of Time magazine in August 1949, with Neutra’s portrait on the cover as he displaced Wright, his former employer, as America’s ‘greatest living architect’.

Kaufmann House, Richard Neutra, Palm Springs, California (US), 1947. Photo by Julius Shulman / © J. Paul Getty Trust

The same year, Shulman was to immortalise the home of designers Charles and Ray Eames that they had built for themselves on a bluff, high above the Pacific Coast Highway on land owned by John Entenza, publisher and editor of Arts and Architecture magazine. The Eameses were well on their way to being the most respected and successful couple in a wide range of design, from industrial design, furniture, film and architecture, to become the Apple of their day. Their house was founded, like Neutra’s Desert House, upon a slender steel frame, but with post-war privations, the steel arrived two years late, allowing the couple to redesign the house, that like Keonig’s house just over a decade later, was to celebrate the industrial components by which it was formed.

The photograph captures the interior of the house with Charles looking for all the world like a Hollywood actor sitting on a curious ankle-height, high backed chair, and Ray, described in her day as ‘a delicious dumpling, in a doll’s dress’, sitting slightly lower staring up at her husband in devotion. In the foreground is their 1956 Lounge chair and Ottoman – the most iconic of all their furniture. The photograph shows their home as a constantly changing collage and an experiment in living.

Glenn Murcutt in front of Marie Short House in 2009, photo by Anthony Browell

My book ends with Glenn Murcutt’s 1975 Marie Short House in New South Wales, Australia – beautifully documented by his own wonderful drawings, along with photographs by Antony Browell (courtesy of the Architecture Foundation Australia). This includes a portrait of Murcutt from 2009 looking out of the house that he had bought from his client five years after its completion in 1975. I had met Murcutt in 1987 on a round the world trip with my long-suffering ‘architecture widow’ Julie, and finding his name in the Yellow Pages (so much in Australia is reassuringly British!) he answered the ‘phone, and as we were his first visitors from the UK, immediately invited us out for lunch. We met in his small office where he worked alone on the other side of the harbour from the Opera House in Sydney and over a lunch in a small café around the corner, he perhaps inadvertently offered my struggling career some advice: ‘No prizes for quitters’. And that has been my journey ever since. So seeing his eyes looking out from the pages at me again in this wonderful portrait is a great joy.

John Pardey, 2020

John Pardey's book, 20/20: TWENTY GREAT HOUSES OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY, is available from our website.

100 colour illustrations and 50 B&W illustrations

ISBN: 9781848223530 • Publication: September 03, 2020