Hans Hofmann: Cataloguing the Abstract

To coincide with a new exhibition of the artist’s works at Crane Kalman Gallery in London this June, Juliana D. Kreinik, contributing editor for the Hans Hofmann Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings, recalls enlightening discoveries of vital information in Hofmann’s handwriten ledgers and the great effort and greater reward of a monumental research publication.

Catalogue raisonné research is a long and exhaustive undertaking. Compiling an encyclopedia’s worth of details requires prolonged periods of hunting, gathering, and organizing. The goal is to find every single crucial missing detail—a name in an artwork’s provenance, the dates and venues of a traveling exhibition, or the page numbers of an article.

As a result, research requires pain-staking and often tedious work. If one takes a deep dive and finds exactly what is desired, and does so in a reasonable amount of time, that accomplishment comes from a smart, resourceful, and dogged effort—and with a great deal of luck. On occasion, however, such research can lead to unexpected results. While completing the Hans Hofmann Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings, published by Lund Humphries in September of 2014, the four-person full-time research staff – of which I was one member – consulted numerous valuable resources. One of the most crucial to the project was a series of three ledgers, kept by the artist and his wife Maria (“Miz”) Hofmann, in which they catalogued most of his painting from the late 1940s until his death in 1966.

Owned by the Renate, Hans and Maria Hofmann Trust, the Hofmann ledgers contain handwritten titles, dates, dimensions, and other basic information about the artist’s works. Until I began a systematic evaluation of the books during catalogue raisonné research, the ledgers had been unexamined and undocumented. Although many artists have kept a record of their output, Hofmann’s ledgers employed a cataloguing methodology: each painting was assigned a unique number, which was recorded in two places: the ledgers, and the reverse sides of the paintings. During catalogue raisonné research, we were able to compare both locations, and the ledgers became a lodestar for the catalogue raisonné research staff.

One example of our many findings: before research with the ledgers, we only knew a pair of paintings in the Philadelphia Museum of Art by the titles Pollux and Castor. When we looked in Hofmann’s ledgers, however, we could not find these names catalogued. The research team examined a dozen different sources of information. Eventually, we deduced that the paintings at the Philadelphia Museum had been known by several different titles since Hofmann created them in 1946. By tracing the titles to checklists, gallery labels, hand written details on each painting’s verso, we determined that Pollux was the same painting as another work in the ledger, called Blue and White. Likewise, Castor was the same painting as a work called Red and White.

While we were certain that the artist had assigned the paintings these very ordinary titles, we did not know how the works came to be named “Pollux” and “Castor,” a reference to twins in Greek mythology. Unfortunately, we never found conclusive evidence of the titles’ origins. We did, however, discover photographs of the two paintings in Charles and Ray Eames’ well-documented home, Case Study No. 8. Since “Pollux” and “Castor” are also the names of the two brightest stars in the constellation Gemini, it seems more than a little significant that the paintings Pollux and Castor were installed hanging from the ceiling of the Eames house.

Could Charles and Ray Eames be the source of these titles? They surrounded themselves with art of the mid-twentieth century in their home. Are there ways in which Hofmann’s work might relate to the Eames’ iconic designs? What other questions do the ledgers and the catalogue raisonné enable us to ask about Hofmann’s work?

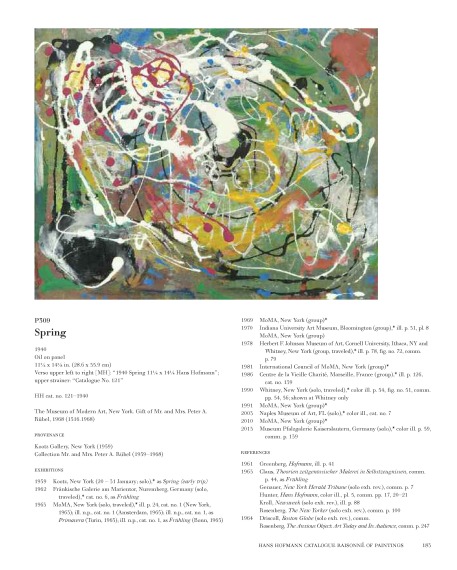

Though the ledgers provided new information in the case of Blue and White (Pollux) and Red and White (Castor), the cataloguing information within the notebooks also helped provide vital clarification for an entirely different type of problem—of dates, rather than titles. According to the artist’s ledgers and other primary source documentation, the artwork Spring was painted by Hofmann in 1940. But the Museum of Modern Art, which owns the painting, dates the work to 1944-45. Why the discrepancy? MoMA had previously dated the painting to 1940. Other Hofmann paintings from 1941 through 1943 demonstrate his interest in experimenting with the technique of dripping paint at this time. Our research gave us no evidence for a date change. But had we missed something?

A long process of examination followed. The research team studied the object record in MoMA’s files, of museum correspondence and verso labels, and other textual evidence, all of which was then compared to Hofmann’s ledgers. The results? We determined that the painting Spring had been re-dated by MoMA curator William Rubin in 1985. [2]

The Hofmann ledgers, however, enabled the research staff to confirm the painting’s date as 1940. We discovered no primary source evidence in our research that gave us reason to conclude otherwise. Adjusting the date of Spring is surely of some importance with regard to Hofmann’s career as a painter. However, its greater relevance is, arguably, the way this and other such findings in the Hans Hofmann Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings enable art historians to ask broader questions of style, development of art movements, and the ways in which institutional discourse evolves.

For instance, how might the date of Spring offer new considerations of the experimental pour and spatter techniques of Jackson Pollock? In One: Number 31, of 1950, owned by the Museum of Modern Art, Pollock’s “drip painting” reaches its revolutionary apotheosis. But Pollock was by no means the first artist to use the techniques of pouring, dripping or spattering, which historians of Latin American art have shown with discussion of Mexican artist David Alfaro Siqueiros’s experimental workshop production in New York City in the 1930s. Hofmann’s Spring and other paintings of the early 1940s indicate that such experimentation with artistic techniques was widespread, and motivated by a variety of factors and forces within and outside of the art world. It is on the occasion of the exhibition of Hans Hofmann’s works at the Crane Kalman gallery that we can once again find new ways to consider the artist’s work, enriching our understanding of his career and its impact on modern and contemporary art history.

Juliana D. Kreinik is the Director of Research at the Cristin Tierney Gallery in New York, where she leads the Peter Campus Catalogue Raisonné Project. Her current independent scholarship examines early 20th century German propaganda postcards, and her essays on the topic will be included in a forthcoming publication with the MFA Boston. She received a B.A. from Wellesley College and Ph.D. from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University.

An Exhibition of Hans Hofmann works is on display at Crane Kalman Gallery, London from 11 June – 11 July